Memes, Emotion, and the Limits of Expression

In the age of widely used digital communication, memes have become one of the most popular ways to express emotions. They spread more quickly than words and are frequently used in online communities as a shorthand for group emotions like humour, annoyance, tiredness, and despair. However, a basic question remains: can memes accurately convey the range and complexity of human emotion, or do they reduce expression to shareable formulas?

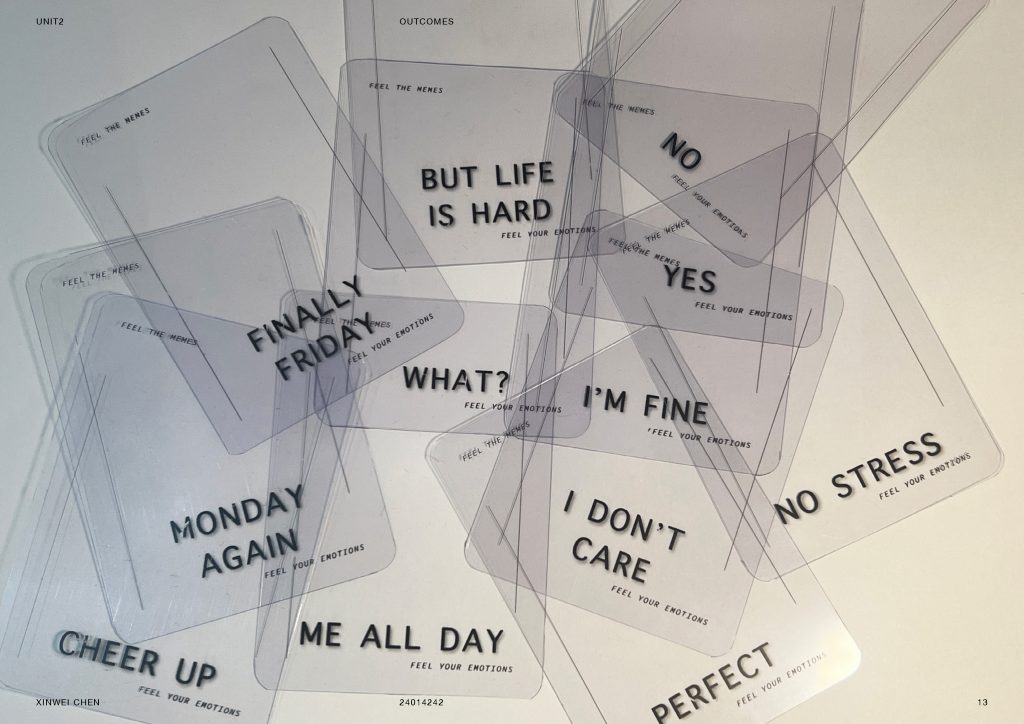

My current project is intended to enlarge digital memes into physical prints and to pair them with PVC question cards that ask audiences to consider the emotional cues they are observing. This gesture transforms an everyday, fleeting digital form into an artefact that invites slow reading, reflection, and dialogue. The experiment takes inspiration from Limor Shifman’s theoretical framework in Memes in Digital Culture (2014). While much criticism views memes as emotionally reductive or homogenising, these scholars suggest that meme templates can function as expressive repertoires — shared visual and textual vocabularies through which affect is produced, recognised, and negotiated collectively. While their theory defends memes as rich social languages, my studio work uses material transformation to question that optimism, exposing the tension between what memes claim to express and what they actually make us feel.

1. Rethinking Memes

Critics claim that memes simplify complex emotions into homogenous reactions. Each viral template, like the “Crying Cat” or the “Distracted Boyfriend,” appears to prescribe a constrained emotional grammar, allowing users to insert new captions into well-known phrases. This perspective holds that meme culture promotes what theorist Stefka Hristova (2014) calls the neutralisation of dissent: political criticism or strong emotions are at risk of being diluted into comedy or irony through frequent remixing. Furthermore, the rapidity and scope of meme dissemination favour immediate recognition over deliberate articulation, fostering a culture of affective shorthand rather than in-depth dialogue.

This presumption is complicated by Shifman’s (2014) three-part typology of content, form, and stance. According to her definition, a meme is a collection of related items that differ in content but have similar form and stance. Every iteration adds to a group discussion that is constantly changing. According to this perspective, emotional expression is found in the network of variations surrounding a single meme instance rather than in that instance alone. Participants are able to use subtle changes in tone, irony, and intensity because of the common structure, or template. For those who are proficient in its codes, what seems reductive from a distance may actually function as a rich affective language.

Nissenbaum and Shifman (2014) extend this argument by describing meme templates as “expressive repertoires.” Through their cross-linguistic analysis, they demonstrate that people across cultures choose particular templates not just for humour or virality but because the template’s visual grammar resonates with certain emotional registers. A crying face, a slanted text box, or a colour gradient can communicate a complex stance — self-deprecation, collective frustration, absurd joy — even before words are read. Memes, then, are not emotionally empty symbols; they are dynamic signifiers that condense shared affect into immediately recognisable codes.

2. From Screen to Space

My point of view addresses the meme as both an image and a social object, building on previous theoretical discoveries. I break the normal scale and temporality of memes by making them larger and printing them as real posters. On a phone screen, a meme’s power lies in its ephemerality: a flash of recognition that travels at the rhythm of the feed. Printing the same image at poster scale freezes that movement. The familiar compression artifacts — pixel edges, JPEG blurs, over-saturated colours — become tactile surfaces. The glossy grain of inkjet paper transforms what was once a casual joke into an object of contemplation.

Each printed meme is accompanied by PVC question cards placed nearby. These cards do not provide explanations but ask reflective prompts such as:

- What emotion do you feel from this image?

- Does this meme speak for you or for someone else?

- If you had to rewrite the text, what would change?

This process reveals a tension at the heart of Nissenbaum and Shifman’s optimism (2014). Their “expressive repertoire” presumes that shared visual codes can approximate shared feeling; my installation suggests that when those codes are slowed down and made tangible, they appear hollow or incomplete. Enlarged and isolated from the scroll, the meme’s affective efficiency gives way to doubt. What once communicated instantly now demands explanation — precisely because its expressiveness was dependent on digital circulation and collective context.

3. Collective but Incomplete Expression

In analysing participants’ responses to the enlarged memes, I expect to observe both the power and the limitations of memetic expression. On one hand, the familiarity of meme templates often allows viewers to instantly identify an emotional stance — irony, fatigue, or helpless humour — even without textual explanation. This supports Nissenbaum and Shifman’s claim (2014) that meme templates enable cross-cultural communication by offering a repertoire of affective cues recognisable across communities. Memes can, in this sense, communicate emotional categories more efficiently than language can.

On the other hand, the PVC question cards make visible the gaps between intended and perceived emotion. Differences arise when viewers openly express their interpretations: some experience true melancholy, while others interpret sarcasm or apathy. This discrepancy shows how incomplete memetic communication is. While templates encode emotion efficiently, they also constrain it within predictable formats. The same image that invites empathy in one context might produce distance or humour in another.

The dichotomy Shifman (2014) notes in digital culture that memes are both collective and fragmentary. They bond users into transitory emotional publics, but the same syntax that allows connection limits expressivity. Thus, memes alternate between solidarity and oversimplification, clarity and ambiguity. My experiment materialises this oscillation by inviting audiences to navigate the distance between seeing and feeling — between the meme’s apparent message and their own emotional resonance.

4. Implications

The project also addresses the materiality of digital emotion by transforming memes into physical scale and integrating them into a participative environment. Emojis, likes, shares, and other data that are abstracted from physical experience are examples of how emotions circulate in online spaces. Printing memes restores texture and weight since the scale, paper, and ink make the effect tangible once again. Viewers’ movements through the exhibition space mimic the “scrolling” gesture but at a slowed, deliberate pace. The PVC question cards, meanwhile, simulate the social negotiation of meaning that occurs online — comment threads, quote tweets, or reply chains — but in a tangible form.

The effort of emotional interpretation that computer interfaces frequently hide is revealed by this tangible translation. Audiences become aware of the collaborative construction of meaning when they are required to select from real cards or create their own answers. In doing so, the project extends Shifman’s theoretical point (2014): memes are not self-contained symbols but social processes. The emotions they communicate are co-produced by users, templates, and platforms alike.

Nevertheless, the experiment also exposes the limits of this process. Even when enlarged and contemplated, memes may fail to capture the specificity of lived feeling. A person’s private grief, anxiety, or rage rarely fits neatly within a templated joke. The gap between personal emotion and public meme underscores what Shifman (2014) calls the “tension between participation and individuation” — the struggle to remain authentic while speaking in a shared vernacular. By making that tension visible, the installation does not resolve the question of whether memes can fully communicate emotion; it reveals that incompleteness as the defining condition of digital affect.

5. Conclusion

Through the theoretical lens of Shifman and Nissenbaum, memes emerge not as degraded expressions but as complex, participatory forms of emotional communication. Their limitations — repetition, simplification, ambiguity — are inseparable from their power to create shared affective worlds. Enlarging and materialising memes, and prompting audiences with reflective questions, transforms everyday digital fragments into an inquiry about how emotion travels between bodies, screens, and social systems.

In the end, the research makes the case that memes do convey emotion, but never completely or exclusively. They are components of a distributed emotional environment that rely on shared literacy to be perceived and comprehended. By lowering their consumption and raising their physical scale, we can observe both their blind spots and their expressive potential. As a result, the printed meme turns into a mirror that both reflects our wish to be understood by common symbols and serves as a reminder that emotion always transcends the templates we attempt to use to convey it.

References

Hristova, S. (2014) Visual Memes as Neutralizers of Political Dissent. Extract pp. 265-276. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v12i1.507.

Shifman, L. (2014) Memes in Digital Culture. The MIT Press.

Leave a Reply